I had not known Art could possess murderous qualities before my encounter with ‘Just Kids’. Patti Smith’s 2010 memoir about her lover and friend Robert Mapplethorpe opens with a prologue announcing the artist’s death over a phone call. At the same time a Puccini aria coincidentally sings out, ‘I have lived for love, I have lived for Art’ from Smith’s gramophone. What is not sung out, but implied through the prologue scene with laconic prose, minimal dialogue and a suppressed tone filled with unspoken howls of mourning, rings in the reader’s mind and captures Smith’s story - ‘I have died for love, I have died for Art ‘. The question of life without art and more crucially, the interchangeable trial of life as art sets the novel into motion. Patti Smith begins her aria about two young nobodies flung into each other's existence in the ubiquitously creative playground of 1967’s New York, and preserves within its pages the enduring memory of a world unchangeably gone.

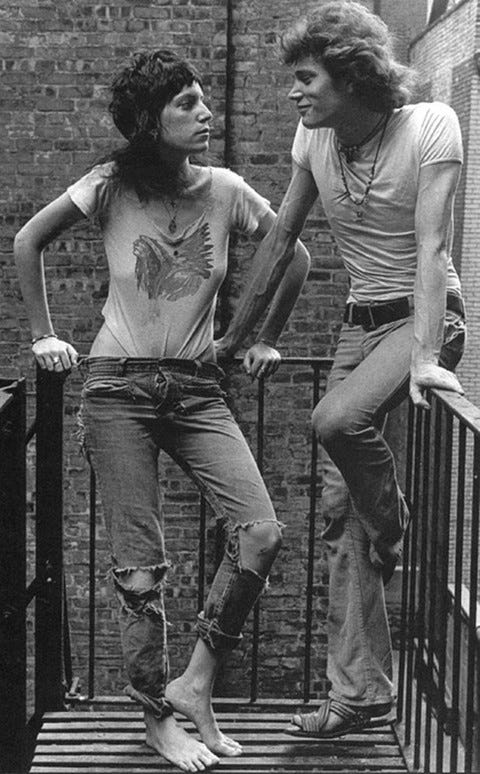

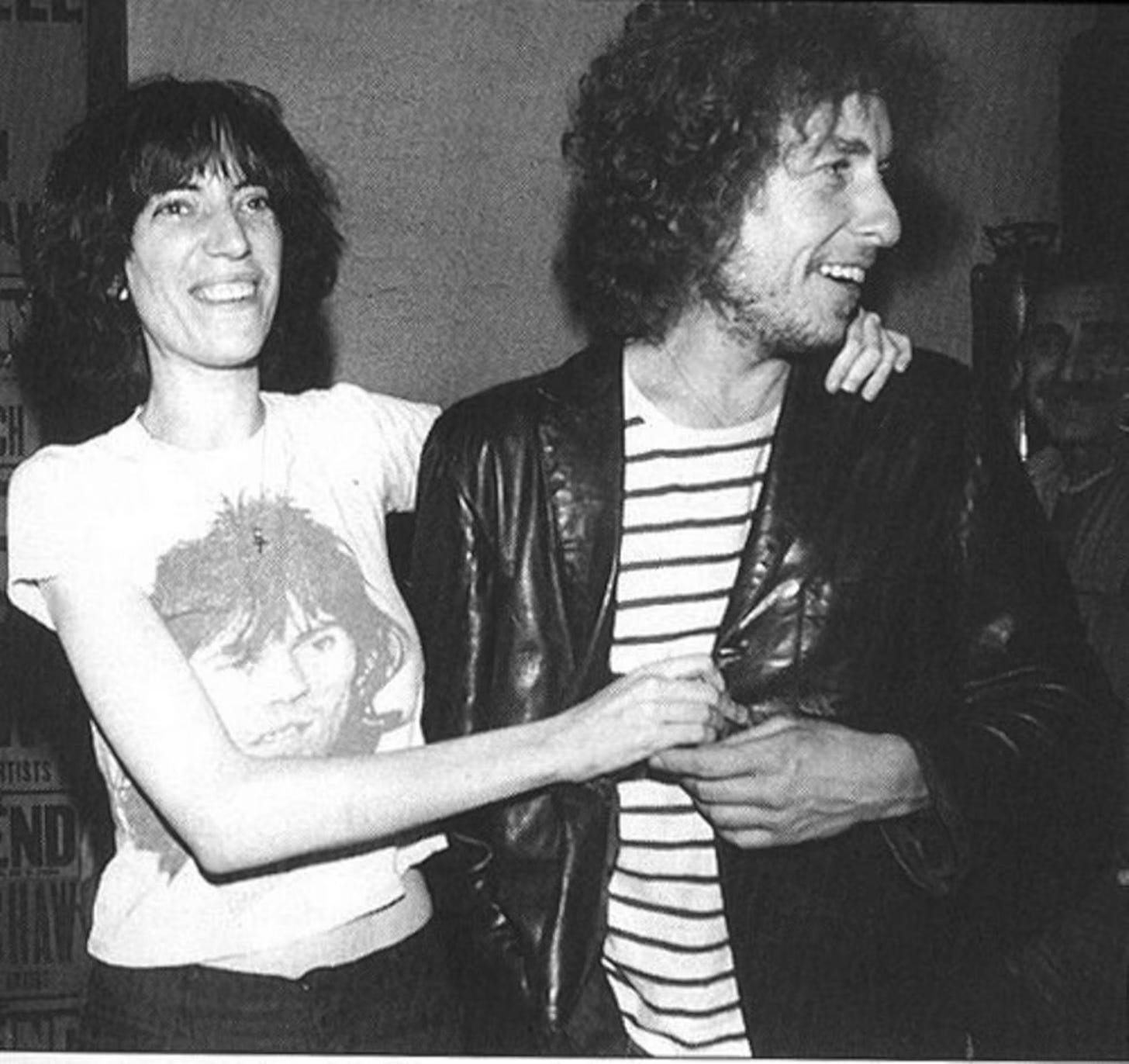

Threaded together by vignettes of Smith’s experience in her youth as an artist in poverty, the memoir is a tapestry of the conversations had by the underbelly of creatives in a city much changed from the present Empire State in which a cappuccino can seldom be enjoyed without bandaging ones bleeding bank account. Each vignette peers into rooms revealing a slower paced, amiable city which was then facing the threat of bankruptcy, and where the perpetually polluted air grasped at the contagious proximity of success. Smith writes of a necessary connection with this city in order to produce her art, wandering round littering her mind with seemingly futile illustrations and poems. It seems that Patti Smith’s New York City was not defined by an infernally busy Wall Street or yellow taxis, but rather its community which at that point comprised of creatives and pseudo-intellectuals in an increasing number. Second Avenue had become ‘Frank O’Hara territory’ whilst a wait in an automat became a brief meal with Allen Ginsberg who buys Smith a sandwich, mistakenly taking her for a scraggy boy. Undeniably the novel is a cornucopia for the biographical literature enthusiast. Smith’s friendship with Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and brief interaction with her totem Bob Dylan all during her impoverishment spoke of an artistic equality and community that placed art as an acceptable cause for struggle. Seemingly, if Smith kept working on her poetry it did not matter that her dinner would be a hand-drawn bread roll if she and O’ Hara walked the same streets, because she was creating with the same belief as Hendrix, that all life for them was already and only their art.

Upon her first week in the city, a companionship with a homeless man over their mutual purpose of ‘living in the universe’ leads to the regular conversation over ‘a real prison breakfast’ - ‘there's water in the lettuce leaves, and the bread will satisfy our hunger’. Smith’s situation in poverty despite her lower middle class family situation in New Jersey in the name of her art, to ‘be free’, is illogical and dishearteningly pretentious in the openings of the novel. The question of art as a justification for struggle due to its integral part of living is difficult to understand. Indeed, when Smith lives with Robert in a ‘place reeked with piss and exterminator fluid’ and a bed consisting of one ‘lumpy pillow crawling with lice’ the novel seems to turn into a tale of life sacrificed for the creative mind. Smith's own narrative consciousness, ‘It was a terrible place ’, the lice ‘mingled with Robert’s damp matter curls’ is strenuous to read and brings a hatred to the artistic cause. Yet Smith’s cause is understood through her companionship with other artists of the period and more so Robert, who himself was prolific in his early collages and photographs. ‘Just Kids’ implies the creative’s hidden view of the world. It did not matter to Smith that she was living in poverty as she could not see it in the same way the reader did. To her, freedom consisted of a derelict living space with no bathroom because she could write, regardless of the lack of profit. For her, even lice were part of her impressionist canvas - ‘ I had seen plenty of lice in Paris and could at least connect them with the world of Rimbaud’. Existing has often had the goal of joy, of happiness provided by financial stability but for Smith art was rapture and so life yearned only for that form of pleasure.

This view of life itself as an artist's notebook filled with regular interactions and inspirational chatter is seen and truly understood through the very medium of the novel as a memoir. Smith’s own narrative of her and Robert’s story becomes art as she lexically embodies the beauty of the mundane - the scuffs on an aged leather boot, the natural coincidences of fortune, and the sublimity of the unrepresentable. The novel becomes an ode to Robert and their story. It turns into literature, into art, a story of two people who never viewed each other as strangers. It is at once painful, frustrating, an ode, a romance, and hauntingly funny. Smith creates art from a recount of the interaction between two lives, and so separates the artist from the intellect who analyses for explanation and meaning in each action, whilst devoid of feeling,

Smith does not analyse situations and derive a hidden definition behind her conversations, and instead urges the reader to merely appreciate what is there, which is often an admiration for the present which is created through her masterfully concise and understated prose. When the end of the novel reaches Robert’s death and ill health Smith records a tender moment between her and Robert:

‘We never had children.

Our work was our children.

…

Patti did art get us?

I don’t know Robert, I don’t know.’

Smith does not celebrate art, yet it is treated as a source of necessity, inevitability. There is no explanation or justification for all the skipped meals and time spent in lice-filled rooms. The unspoken justification is that of a rather simple belief in existing. Smith reveals the hidden veil of sight that her and the many other artists in the city recorded through merely walking. It is this perception of feeling, of passion, of lust, of maelstrom that cannot be exactly analysed. Indeed, Robert tells Patti, ‘I don't think [...] I feel’.

There is much I have wanted to but not said about this memoir in avoidance of ruining the action of the story. I have not written on the pure love, and complicated companionship between Robert and Patti, and instead chosen to criticise the points of contention within the easily mistaken pretentiousness of the novel. Yet, I will say the novel’s portrait of a man through the mind of his lifelong creative partner is not one I have found before, and I hope to find it again.